Benge is Ben Edwards, best known for his role as Chief Mathematician and collaborative partner in JOHN FOXX & THE MATHS.

Their album ‘Interplay’ was one of the most acclaimed electronic pop albums of 2011. It was swiftly followed-up by a second album ‘The Shape Of Things’

and an extensive UK tour featuring BENGE cohorts Serafina Steer and Hannah Peel, leading to the project being voted Best Electro Act of 2011 by Artrocker Magazine.

And before there was time to blink, there was a third instalment ‘Evidence’, a tour support slot for OMD and a live album ‘Rhapsody’

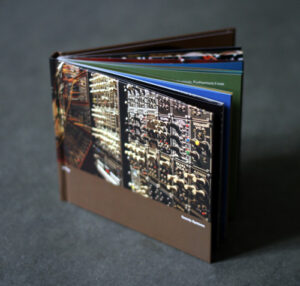

in 2013. Developing on a childhood fascination with electronic sound, after finishing art school, Benge set up a music studio and released his debut album ‘Electro-Orgoustic Music’ in 1995 on his own Expanding Label. Since then, Benge’s recording complex has become the now famous Play Studios which houses one of the largest collections of working vintage synthesizers in the world. Several of these appeared in the BBC documentary ‘Synth Britannia’.

He also worked on a variety of projects with other artists and released a further nine experimental solo albums, the most acclaimed of which was 2008’s ‘Twenty Systems’. It is an insightful soundtrack exploring how electronic sound architecture has evolved from using transistors to integrated circuits and from ladder filters to Fourier approximation.

Brian Eno described it as “A brilliant contribution to the archaeology of electronic music” while it was via this album that Benge first came to the attention of John Foxx. With the reissue of ‘Twenty Systems’, Benge was in the Moog for a chat…

How did you first become fascinated by electronic music?

I was born in the late 1960s and grew up in the 1970s when my parents ran a small independent school from our family home. It had a music classroom full of stuff like tape machines, electric organs, percussion instruments and even a modular synthesiser that was donated to the school by a family friend.

It was hand built in the early 70s and we called it The Black Box. As a boy I would spend hours in the music room with headphones on experimenting with sounds. When I got back into synths after I went to college, I asked my dad what happened to The Black Box and he said “oh, I chucked it out a few weeks ago!”

Who were your favourite artists and did you like the ‘Synth Britannia’ era?

When I was a teenager, I listened to any music with synths on, from Prog Rock to Stockhausen to KRAFTWERK. The first gig I ever went to was GARY NUMAN in the late 1970s and it blew my mind. What is really cool about that is the support band were OMD (it was just two of them and a tape machine back then) so they were actually the first band I ever saw live, and we have just finished a support tour for them.

What was your first synth and is it still part of your armoury?

The first synth I ever bought was an Octave Cat mono synth for £30. I sold it for £40 to buy a Moog Prodigy which I sold for £60 to buy something else, I think it was a Yamaha CS40M. That was pretty much the last synth I sold.

How did you start actually collecting synths and what criteria did you use to decide what you acquired?

It was very different back in the early 1990s when I first got into buying stuff. People were literally chucking equipment out and I would go around getting pretty much anything on a whim. At first, I never paid much for things, but as I got more discerning I suppose I went for the more quirky and unusual things, like the modular instruments or large scale digital systems.

Your reissued 2008 album ‘Twenty Systems’ is an aural history of the synthesizer. When you had the original idea, did you already have everything you needed or did you have to plug-in the gaps so to speak?

I had had the idea to make an album using only one synth per track and had started to record it. Then one day I was sitting in the studio and I wondered if I had enough synths to do a set of consecutive years. It was very exciting because as I looked around I suddenly realised that I had the years between 1968 to 1988 covered – and as I explain in the booklet, these are the years that take us from the first analogue instruments to the large computer based workstations – in other words, the most important era of development in this field.

Where did you find the Moog Modular and what is the history of your particular example?

I got the Moog 3C system in 1994 from a guy called Martin Newcome. He had recently set up a place called The Museum of Synthesiser Technology and as a result he had a lot of contacts in the synth world, and in particular the American dealers. I asked him if he could source a Moog system and he obliged, but it meant that I didn’t find out its provenance. It’s a pretty early system from around 1968, and it’s got the nice early oscillators.

Only the synth mentioned in the title was used on its corresponding track; but with the EMS VCS3 one, you used the delay section of an EMS Polysynthi. Vince Clarke declared the Polysynthi as “the worst sounding synth ever made”. I’m no expert but I have tried one and I think it sounds horrible too… what’s your take?

Only the synth mentioned in the title was used on its corresponding track; but with the EMS VCS3 one, you used the delay section of an EMS Polysynthi. Vince Clarke declared the Polysynthi as “the worst sounding synth ever made”. I’m no expert but I have tried one and I think it sounds horrible too… what’s your take?

I am aware of the limitations of this synth, but in a way that’s what I like about it – it has its own very unique character and to me that makes it interesting.

For example it’s the only synth I can think of with a voltage controlled analogue delay built in to the audio path. Generally speaking, I say the more quirks an instrument has the better, otherwise all electronic music would sound the same!

The later tracks feature the digital computer synths such as the PPG Wave, Fairlight, Yamaha CX5M and Synclavier. As someone who is renowned for his love of analogue, how do you look back on this era of electronic music?

Actually I have just as much passion for digital equipment as analogue. The analogue/digital debate has never been an issue for me. The Fairlight is possibly one of the best synthesisers ever designed, regardless of its role as a sampler – people forget it can do 32 part additive synthesis in real time – not bad for 1983. And the Synclavier has a digital conversion rate of up to 100k which makes it sound so big and warm, or equally bright and dynamic. Again all these various systems took a very unique approach to sound creation and that’s what gives them so much character.

Of the ‘Twenty Systems’ tracks, which do you think was the most successful conceptually?

I think the ‘1987 Synclavier’ piece is the closest to what I wanted to achieve with the tracks on the album – namely to let the machine be as big a part of the composition of the track as possible. On that track I really set the machine up in a way that brings something of its character out over a wide range of sounds and compositional techniques. However, my favourite piece on the album from a musical point of view is the ‘1975 Polymoog’ track. There is something about the combination of the simple melody and the tone of that keyboard that seemed to work together well.

Did that match up with what was your own favourite synth? If not, what are your favourite all time synths?

Neither of those tracks was made on my favourite synth which has to be the Moog Modular. That gets used nearly every day. It has such a big and powerful sound that has still never been bettered by any of the synths that have come since. However I recently bought a vintage Buchla 100 which was made at the same time or perhaps a few years before the Moog and I have to say it is as good as the Moog, although it does things in a very different way. It’s got a raw power to it that is like listening to pure electricity coming out of the speakers.

What inspired you to work with John Foxx and how would you describe your creative dynamic with John?

Well, John has been one of those figures in music who has inspired me so much over the years to remain creative and be true to my beliefs as a musician and producer. When I was first introduced to the idea of working with him, I was so happy. I think John was attracted to the idea of working again with all these original synthesisers, and he also liked the purity of the sounds I was getting out of them and the simplicity of the approach I had taken on ‘Twenty Systems’.

We have a lot in common when it comes to what we are looking for when we make our tracks together. Neither of us are actually keyboard players as such but we see this as a positive thing because it means we have to rely on the analogue sequencers and arpeggiators to play the melodic parts. Neither of us can play complicated chords or tricky solos but this gives our tracks a certain simplicity which we really like.

How different is it from what you understand about his methods when working solo, or with people like Louis Gordon or Harold Budd?

I don’t know much about his working practices with other people, but for us it’s all about exploring new possibilities and trying to capture something special in the studio. The first album is called ‘Interplay’ and if you listen to the title track you will learn a lot more about our working practices than I can tell you here!

‘Interplay’ has been considered by many to be the warmest album that John Foxx has ever made. How did you both set about achieving this? Is it largely down to using vintage equipment or is it more than that?

We both have an affection for the impurities contained within sounds, the little things that give life to electronic equipment and computers. I find that old equipment has a lot more of these quirks and imperfections inside them, and these things build up when you layer and reprocess sounds, if you allow them to do so. It’s about embracing the foibles inherent in the equipment and using them to your advantage. Maybe it is this that gives it warmth and a certain organic quality.

For example, the oscillators on the Moog system drift slightly out of tune all the time, and when you layer them up you can hear them slightly ‘beating’ with each other. But this gives the sound a wonderful shimmery, edgy quality that you don’t get with perfectly tuned synthesiser voices.

‘The Shape Of Things’ is a much starker, more reflective collection. How did you manage to finish a second album so soon after the first one?

We spend a lot of time down here in the basement! Also there have been a lot of collaborations with other artists coming into the equation since I have been working with John. There’s always something going on here and most of it gets recorded and has found its way onto our records. It’s a very exciting time to be in electronic music.

What memories do you have of the first time you played live with John Foxx at The Roundhouse in 2010, especially with all that vintage gear on stage?

It’s always scary using modular stuff on stage. At The Roundhouse, we had quite a bit of it up there and also we used CV and Gate to connect up the drum machines, sequencers and arpeggiators which added another level of uncertainty. But it all worked out as we had hoped for with only a few minor issues. I like using this approach if possible – it certainly keeps it exciting. I’ve got another project called WRANGLER, with Phil Winter and Mal (ex-CABARET VOLTAIRE) and we have done a few small gigs in London without using a laptop – it’s all analogue – clocked from CV and Gate.

What have been your favourite tracks from the JOHN FOXX & THE MATHS project?

My favourite tracks I think are the really simple ones where there is just a modular synth sequence and drum machine and John has come in and written his vocal around it – so a perfect example would be ‘The Good Shadow’ from the first album or ‘Talk’ from the second. On the other hand, having played our stuff out live so much recently I have begun to appreciate some of the more full-on songs such as ‘Catwalk’ and ‘The Running Man’. They have been the highlights of the live set for me, especially as a drummer.

Of course, JOHN FOXX & THE MATHS toured with a more streamlined hybrid set-up. How satisfied were you from a production point of view with how it all sounded?

It’s quite a different beast now we are a threesome – but it’s great fun and feels like a really tight unit. Its hard for an electronic band to perform sequenced material live without a backing track, so we have gone for a combination of using some of the studio-recorded synth sequences and drum machine parts (including the ‘Metamatic’ stems taken from the original 8 track masters) with the live vocals, keyboards, violin and Simmons drums. I think it’s pretty unique and a really fun way of presenting our material.

So what do you think of these modern analogue synths such as the Moog Voyager and Dave Smith Prophet 08 which have their heritage in classic instruments?

I find it very exciting that there is now a booming analogue synth industry. There are more modular manufacturers around today than ever there were in the 1970s, which is a huge surprise. It’s a reaction against the dominance of plug-ins and apps. For me personally I still prefer the older, wonkier equipment though. There’s something about the sound, feel and smell of the older stuff that really appeals to me. Someone should design a synth plug-in that smells right.

And what’s the next synth that you’ve set your heart on getting, either vintage or current?

I’m always on the lookout for stuff naturally, but I try and remember that these things are only there to serve a purpose – to make music! So alongside my work as THE MATHS, I have been busy recording a series of more experimental electronic albums over the last year or so. They tend to be focussed on a particular synthesiser or system, such as the Buchla, and can be found over on my Bandcamp page: http://zackdagoba.bandcamp.com/

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its warmest thanks to Benge

‘Twenty Systems’ is re-released as a CD via Expanding Records

http://myblogitsfullofstars.blogspot.co.uk/

http://playstudios.carbonmade.com/

http://www.expandingrecords.com

http://www.johnfoxxandthemaths.com/

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

Photos from Benge’s websites and artwork except where credited

24th June 2013

Follow Us!