Richard James Burgess is the renowned record producer who famously coined the term New Romantic.

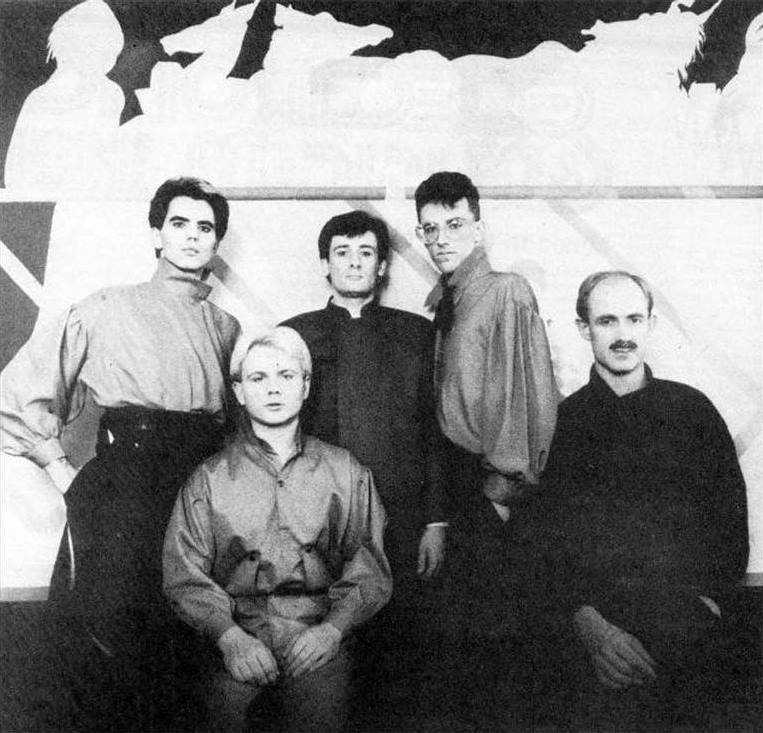

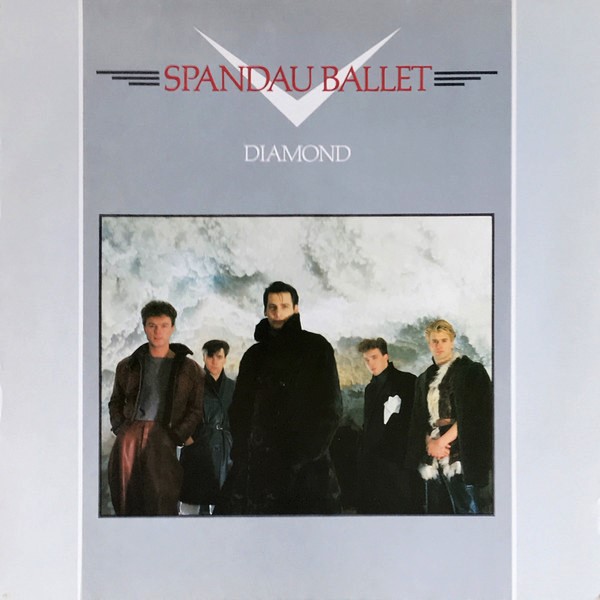

His triumphs from that era include the brilliant 12 inch Special Mix of ‘The Freeze’ and the glorious neo-classicism of ‘Musclebound’ by SPANDAU BALLET. The Islington quintet’s earlier, more electronic sounding work was all produced by Burgess. There was also his Fairlight work on the linking interludes on the first VISAGE album.

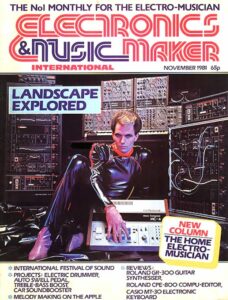

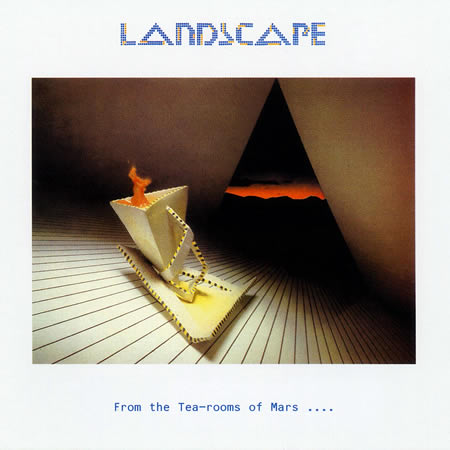

A winner of numerous production awards, his book ‘The Art Of Music Production’ is an international best seller. He is also a successful musician in his own right with the group LANDSCAPE who scored their biggest hit ‘Einstein A Go-Go’ in early 1981. At the forefront of studio developments such as the Roland Microcomposer, the Fairlight CMI and his own Simmons SDSV, Burgess appeared on the BBC’s ‘Tomorrow’s World’ on no less than three occasions to demonstrate these wonders of musical technology that without doubt changed music forever.

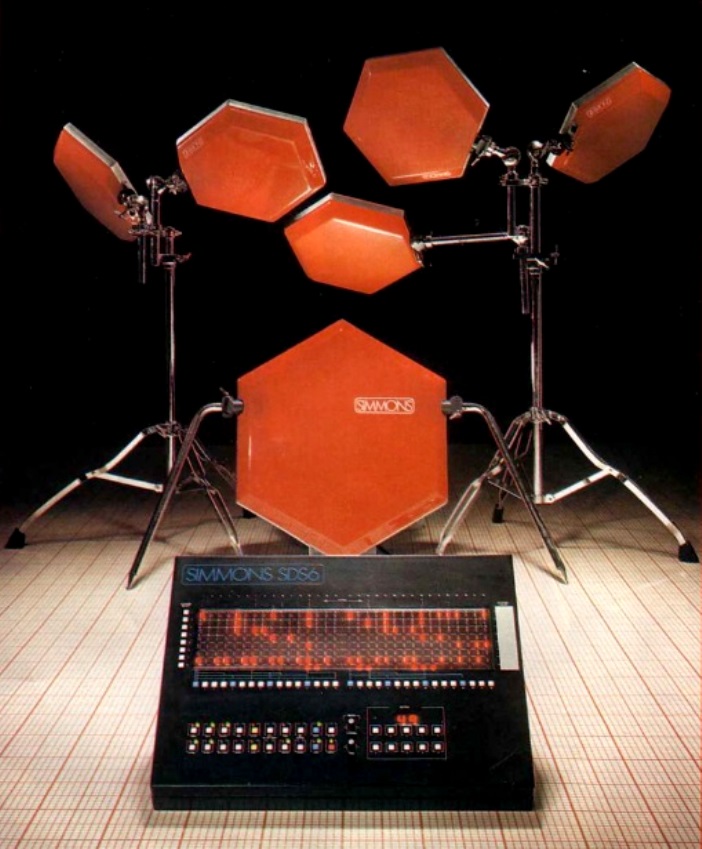

It is the Simmons SDSV that could be considered Burgess’ biggest contribution to music and popular culture. Conceptualised and co-designed with Dave Simmons, it was the first standalone electronic drum kit where the individual parameters of each sound could be adjusted. The original idea had been to make a machine which could be played by a drummer as a replacement for acoustic drums and was developed from having to deal with the problems of audio spill via microphones when playing drums live. Sounds were originally mocked up around an ARP 2600 synthesizer which had already been popular with producers such as Martin Hannett and Daniel Miller for being able to obtain distinctive but useable percussive palettes.

A prototype of the SDSV triggered by a Roland Microcomposer was used on singles by SHOCK and the LANDSCAPE album ‘From The Tea-rooms of Mars To The Hell-holes Of Uranus’. But the full kit itself did not appear on a recording until SPANDAU BALLET’s ‘Chant No1’ in 1981. The hexagonal pads, made from material used in police riot shields, became an iconic image while the distinctive synthetic “dzzshhh” sound (which Burgess modelled on the way he tuned his Pearl concert toms with one tension rod loosened causing the pitch to drop after the initial hit) became ubiquitous featuring on records by ULTRAVOX, DURAN DURAN, TALK TALK, CLASSIX NOUVEAUX, THOMAS DOLBY and A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS among many.

Now based in Washington DC where he works as Director of Marketing and Sales for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, Richard James Burgess recently paid a visit to the UK and hooked up with his old mate Rusty Egan from VISAGE and The Blitz Club. He took time out from his busy schedule to talk at length about his pioneering career.

How did you first get into record production?

I bought a portable Tandberg tape recorder when I sixteen and recorded everything that made a noise. I actually studied electronics at college before I went to Berklee and Guildhall for music and then I owned an EMS Synthi A synthesizer and bought myself a Revox tape machine that I used to record almost every LANDSCAPE gig. In the mid-70s when I was in the group Easy Street signed to CBS and Polydor Records, we used to produce our own demos in high end studios all over London and I was working with wonderful producers as a studio musician and in the various bands I was playing in.

At first producing didn’t appeal to me because it involved such a lengthy commitment of time to a single project but when I started making music using the MC-8 Microcomposer, I realized that none of the producers and engineers had any understanding of how to deal with that technology and what was about to become the new way of making records.

LANDSCAPE had recorded one track ‘European Man’ for what would become the ‘Tea-rooms of Mars…’ album with Colin Thurston and we realized that it would be easier to produce the record ourselves because we understood the underlying thinking of computer generated music. We were putting most of it together at my home studio and then just dumping it to tape at the studio anyway.

So the ‘Tea-rooms…’ album would be the first commercial co-production (with the other members of LANDSCAPE) that I did, but we held it back until after the SPANDAU BALLET ‘Journeys to Glory’ album came out. Spandau’s manager Steve Dagger called me out of the blue and asked me if I wanted to produce their first album.

I was very excited about that and I had seen the band at nearly all of their first six gigs. I knew them personally from The Blitz and liked them. I also knew that we could make a great album that would be a hit and that the LANDSCAPE album would be more likely to chart if I had a hit with SPANDAU BALLET first.

The confidence of youth is a beautiful thing and it all worked out very well. The ‘Journeys to Glory’ album immediately went gold and launched my production career. It nearly ended my career as well because all I was offered after that was artists who wanted to sound just like SPANDAU BALLET and I preferred to work with artists who are fundamentally original.

The new remastered sound of ‘Journeys to Glory’ is really quite shocking. As the producer, do you have an opinion on this and this trend for loudness and brickwalling in mastering?

I am not sure I have the same version you do and I don’t listen to my old stuff at all unless I have a reason to do so. Labels don’t bother to call the original producer about these things and who knows which masters they are using. I stand strongly opposed to brickwalling in mastering. It existed in vinyl mastering too – everyone was trying to make the loudest record. What makes no sense about this practice is that it doesn’t matter – radio compresses and EQs the life out of everything anyway so destroying the sound of your production to make it a couple of dB louder is irrational. If you are listening in the car or at home you can just turn it up a bit if it seems quiet.

‘Diamond’ has come out much better and it occurred to me how the second artier side is a very under rated. The track ‘Innocence & Science’ in particular isn’t really that different from JAPAN’s ‘Ghosts’. Many who have never heard this would be surprised to learn it’s SPANDAU BALLET. How did you achieve those naturalistic sound textures like the cheng, sitar, vocal drones, water drips, ethnic percussion etc? Were those courtesy of your Fairlight?

Thank you. My recollection is that this was about the time I stopped reading my press. If I recall correctly, we got slammed for the B side – some reviewers thought it was pretentious. It was Gary Kemp’s idea, I loved it. There is no Fairlight on it at all. We did it at Jam Studios in North London and we played or created all those sounds naturally, the huge sounding concert bass drums were courtesy that amazing huge old room (it used to be a Decca classical soundstage).

I felt that we were naturally progressing – ‘Chant No1’ signalled the move from the initial sparse, New Romantic sound into the funkier sound that many other groups picked up on and that B side of ‘Diamond’ was pushing into atmospheric, world kinds of sounds. As you have success, it seems like a good opportunity to stretch and take risks.

LANDSCAPE started as primarily as a jazz funk fusion group. Was there a particular moment when you and the group decided to pursue a more synthetic direction?

As I mentioned I had a strong grounding in electronics and Chris Heaton (keyboard player in LANDSCAPE) and myself had an avant garde electronic group (ACCORD, with Chris on treated and prepared piano, Roger Cawkwell on synth, myself on homemade electronic percussion and sometimes Chris’s brother Roger Heaton on clarinet). I had been fascinated by the computer music experiments going on at Stanford and IRCAM (John Chowning etc) and when I heard about the Roland MC-8 Microcomposer, John L Walters and myself immediately went out to the Roland warehouse to play with it and I bought one.

I had been working on what would become the Simmons SDSV drum synthesizer and had been using electronics triggered by my drums for several years (as can be heard on the first LANDSCAPE album on RCA). I had been playing around with several concepts for electric and electronic drums and had built a bunch of prototypes which I used on gigs. LANDSCAPE had sold about 25,000 EPs of our live recordings, U2XME1X2MUCH (pr. you two timed me one time too much) and ‘Workers Playtime’.

I don’t know what the first LANDSCAPE album for RCA sold but it didn’t chart in any big way. Rusty Egan was playing several tracks from it at The Blitz, in particular the lead track ‘Japan’ which featured treated piano, electronically altered soprano sax and trombone and electronic triggers on the drums.

I also used Moog Drum on ‘The Mechanical Bride’ from the album and other bits and pieces I begged, borrowed and made myself. I had used very early electronic percussion on the EASY STREET recordings in the mid-70s: the Impakt Percussion device and I used my Synthi A to mock up percussive sounds.

We had all or most of the music written for what would become the ‘Tea-rooms…’ album and I was sitting at home thinking and I realized that we were going to get the same result as we did with the debut album if we put out another instrumental jazz-funk album through a major label. We discussed it in the band and everyone was on board so I started working on the lyrics that became ‘European Man’ (over a track we called Route Nationale). John and I worked up ‘Einstein A Go-Go’; everybody in the band wrote and arranged so we reconceptualised that album.

We rehearsed the music and recorded those sessions, I wrote out my drum parts and programmed them for the MC-8 Microcomposer and the prototype SDSV drum synth. John and I programmed many of the other parts too and the rest we played using mostly altered or synthetic sounds. By this time I also had one of the first three Fairlight CMI samplers to leave Australia (Peter Gabriel had one, Syco Systems who sold them had one and I had the other) and we were very close to putting a track on the album featuring that instrument but in the end decided that the album was complete without it.

I think we all embraced this new direction because of our raw excitement over the new technology and the seemingly endless possibilities for new sounding orchestrations along with the realization that we weren’t going to be able to survive at RCA if we kept making instrumental jazz-funk recordings.

Electronic pop music was often seen as pompous and pretentious by the general public, but it always seemed LANDSCAPE had their tongues firmly in their cheeks as evidenced by ‘Einstein A Go-Go’, ‘Norman Bates’, ‘Eastern Girls’ and the album title ‘From the Tea-rooms of Mars to the Hell-holes of Uranus’! Do you think this all went over the heads of most people?

I am so glad that you understand this. The clothes (vinyl suits!), much of what we did was tongue in cheek. We were serious about the music and production but we understood the inherent ironies and challenges of being an odd looking band with a very non standard line-up trying to make a living and even hit the charts.

It did not appear to me that the humour, irony and cynicism were ever picked up on by the media. I did see a recent review of ‘Einstein A Go-Go’ that mentioned that the song is a cautionary tale about the apocalyptic possibilities of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of theocratic dictators and religious extremists. We talked about the track conceptually before we wrote it and our objective was to make a very simple, cartoon-like track with a strong hook that would belie the meaning of the lyrics!

You were very close to the scene at The Blitz and are credited with coining the term New Romantic. How did this come about and why do you think this has stuck when other descriptions like ‘The Cult With No Name’, ‘Blitz Kids’, ‘Peacock Punks’ and ‘Futurists’ etc fell by the wayside?

I always believed that for a movement to stick and be identifiable it needed a name. We had just been through punk and glam. Initially I was using three terms Futurist, Electronic Dance Music (the LANDSCAPE singles have EDM printed on them) and New Romantic. My feeling was that the first two terms applied to LANDSCAPE and bands like ULTRAVOX but SPANDAU BALLET was the pre-eminent band for the new movement and New Romantic really applied to the dandyish dress styles of not only Spandau but the whole Blitz look. The look was what caught the attention of the worldwide media – it was such a contrast with punk.

Even Adam Ant (I produced him later in 1983) who had been around for several years by that time got roped into the New Romantic category in America because of his look. The track ‘Face of the Eighties’ on ‘Tea-rooms…’ was a reference to the phenomenon. Once the other bands like CULTURE CLUB, DURAN DURAN, HUMAN LEAGUE broke and then the next generation kicked in such as HAIRCUT 100, KAJAGOOGOO etc, the die was cast.

You were at the forefront of new technology with developments such as the Roland Microcomposer, Fairlight CMI, Lyricon and the Simmons SDSV electronic drum kit. How exciting was this period for you, particularly with the Simmons which has now become so iconic that LA ROUX has an unplugged bass drum pad as a stage prop?

It was incredibly exciting without question, but I don’t think I could really appreciate what was happening fully because I was so busy – and that was exciting to be in demand and working with great people so much. I tend to be forward looking and think about what’s next more than thinking about what has been, so once it all happened I was definitely in ‘next’ mode.

Was the futuristic looking hexagonal shape of the Simmons pads your idea?

Yes it was. I was driving up to St Albans where Musicaid was based (that was the name of the company before they went bankrupt and Simmons was formed) and I was thinking about what kind of shape the pads should be. I realized they didn’t need to be round. The first prototype was triangular (I still have that) but I wanted something that would fit together well in a drum set and it struck that the honeycomb is an organic shape that locks together. Dave Simmons made bats-wings and the Rushmore Head set (I have two of those) but in the end it was the hex shape that caught on.

I mentioned to Rusty Egan that the SHOCK B-side ‘RERB’ was one of my favourite tracks of his. You co-wrote and co-produced it with him, can you remember how this magnificent track came about and were you ever disappointed it never gained the recognition it deserved as a classic electronic dance track?

We wrote that in about ten minutes at my home studio in London. It was made as a B-side for ‘Angel Face’ so I didn’t have any major aspirations or expectations for it. My MC8 / System 100M setup was always ready to roll; we talked about what we wanted and it popped out complete.

I think SHOCK, in general, suffered from being too early, as did LANDSCAPE. A couple of years later there were radio stations all over the world that would play this stuff and many more clubs but this was still the end of the disco era and the new wave era, we were limited to cutting edge DJs in London, NYC and LA and very little else.

To see SHOCK perform that stuff on stage in a packed show at The Ritz in NYC was an electrifying experience, and it really fed the excitement of the early adopters but there just weren’t enough of them, worldwide, at that time for it to gain mass acceptance. Many of the people at that Ritz gig and their other gigs became movers and shakers in the 80s scene – it was as if this was the kind of music and the look they were waiting for.

Your production credits also include KING, Adam Ant, Virginia Astley, Kim Wilde, WHEN IN ROME and PRAISE. As well as that, you did Fairlight programming for Kate Bush and VISAGE. Did you have any particular favourite acts who you worked with and memories you can share?

I can’t say enough good things about Kate Bush. She was always wonderful to work with, incredibly talented and an innovator. She called us about the Fairlight – she found out about it through Peter Gabriel and she fully grasped the implications of what it could do immediately. Kim Wilde is an absolute sweetheart and that was a fun record to make in Los Angeles. Virginia Astley was a really different record for me and she had a strong vision which is something I really look for in an artist.

I did the VISAGE programming at my home studio and recorded it at Mayfair and that was fun because of all the guys in the band who were setting the trends in the Futurist / New Romantic scene, there was a feeling that we were treading new ground. WHEN IN ROME I did in LA and I am still in contact with those guys – nice people and a lot of fun.

I felt that PRAISE really set the ambient music compass, Geoff MacCormack and Simon Goldenberg really defined that world music and wordless vocal sound. As successful as the record was, I don’t think they got the credit they deserved. Records can be hard to make for many reasons, personality clashes and creative differences being among them but I really felt fortunate in being able to work with great people.

LIVING IN A BOX were great. SHREIKBACK was tough because Barry Andrews didn’t really want to make a record that commercial and I can commiserate with that, but that’s what Island Records brought me in for and we wound up with three or so tracks in the Billboard modern rock charts simultaneously from ‘Go Bang’.

It would be true to say that I got a lot of satisfaction out of the Colonel Abrams tracks I cut, particularly ‘Trapped’ and ‘I’m Not Gonna Let’. I produced all the hits that he had and some people say that we defined the early house music sound.

I had just moved to NYC and I didn’t have much equipment with me – a LinnDrum, DX7 and a Juno 106 and I made the record with just those instruments. The special factor there (apart from Colonel’s incredible voice) was Colonel and Marston’s NY street sensibility combined with my radio production perspective and programming sensibility and we got something that really took off.

How did you feel when Stock Aitken and Waterman basically ripped ‘Trapped’ off for Rick Astley’s ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’

It’s funny, I didn’t even know until LIVING IN A BOX pointed it out to me. Frankly, I take it as a huge compliment. SAW are very capable writers and for them to build a completely new song and create another big hit off of one of my bass lines just points up the incredible breadth of possibilities available even in a specific genre like dance music.

You and John L Walters from LANDSCAPE originally produced HOT GOSSIP’s debut album in 1981 which Dindisc Records didn’t release and it was eventually completed with HEAVEN 17’s Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh. But Andy McCluskey from OMD who were also signed to Dindisc at the time was particularly uncomplimentary about you in the music press. Did you ever get to the bottom of why he had such venom and did you ever bump into him to err… discuss the matter?

I made a decision right after my first big success as an artist and producer not to read my press. So this is the first I am hearing about Andy McCluskey’s negative comments. All I can say is that I am really good friends with Mike Howlett who produced those OMD records and I hold him in very high regard. I don’t know Andy and I have no understanding of why people can be negative like that about someone and something they know nothing about.

I also met Martyn Ware recently and like him immensely; clearly we have a lot of shared interests and history. I will say that I think the HOT GOSSIP record that I made with John L Walters was one of my favourite productions. I haven’t listened to it in nearly thirty years, but my recollection is that we really broke some new ground.

Unfortunately I think what Carol Wilson (the A&R person) and Arlene Phillips (HOT GOSSIP) were looking for was something more like SHOCK, LANDSCAPE, SPANDAU BALLET and I used Harvey Mason Jr on drums, Gil Evans played piano on it (that is a great story) and David Sanborn played sax along with many other amazing musicians. I was young and somewhat naive and I played the roughs to Arlene and the label all the way through the process; everyone was nothing but enthusiastic and yet when I turned in the mixes, it all went horribly south.

With a couple more years of experience under my belt I might have been able to right the ship, but they just went ahead and remade the album without any meaningful discussion. This was a huge learning experience for me and rocked my confidence for a bit. With regard to negative press in general, I think it’s inevitable once you have major success that the knives will come out. Artists attacking artists – especially ones they don’t personally know – seems unnecessary. There was a period where I could do no wrong and another where I could do no right in the music press’s eyes.

What would you say was your proudest artistic or technological achievement?

Some of the moments I am proudest of are ones that were ephemeral: gigs in the early jazz-funk phase of LANDSCAPE. I am a musician, a drummer – I still play regularly- to play with great musicians really excites me. I was never driven by money or success, although both are good and necessary in order to keep making music. There were some specific gigs I remember that were incredibly exhilarating, I am thinking about The Stapleton in Crouch Hill and the Music Machine before it became the Camden Palace (we used to jam that place), the guys in LANDSCAPE were so great to play with. I am still happy with ‘Einstein A Go-Go’ and the whole ‘Tea-rooms’ album.

I am still comfortable with what I did with ‘Chant No1’, ‘Trapped’, ‘Living In A Box’ and many other tracks I produced. I wanted to keep challenging myself and once everybody else starts doing something, it tends to lose its appeal for me so that we made the first computer driven hit single and album with the MC-8 (‘Einstein’ and ‘Tea-rooms…’) the Fairlight stuff with Kate, the SDSV for sure, ‘Trapped’ felt like we were pioneering again, PRAISE seemed like new territory at the time also.

The early programming stuff in the 70s was incredibly exciting, if equally tedious. We were programming drums in machine code – ons and offs – the other parts were just a series of numbers; three to define one note. Although it’s not remarkable at all today, to be able to stand back after hours and hours of programming and watch this thing that looked like an adding machine play your compositions and arrangements was an unbelievable thrill.

Oh, three times on ‘Tomorrow’s World’ was fun.

You are now Director of Marketing and Sales for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings in Washington DC. What does this involve? And how do you feel about records such as MOBY’s Play and 18 which sample a lot of traditional gospel and folk recordings as their conceptual basis?

The original intention of copyright law was to protect a work for a period to allow the artist to benefit and then to make that work available for others (preferably after the artist is dead). Montage and collage has been around for a very long time in the visual arts, I have no problem with people sampling other people’s work and creating a new work. If the work is still in copyright then a license should be obtained and the creator should be compensated fairly. If the creator is still alive, they can always decline the license if they don’t approve of the use. I do think copyright law for sound recordings needs to be standardized internationally and I don’t agree with the fifty year law in Europe – at the very least the artist’s lifetime should be covered. Artists can always issue Creative Commons licenses if they so desire.

Your book The Art Of Music Production was a big seller and is still going strong. How do you feel about modern production techniques and how they’ve developed? Are there any of new generation of producers who you rate?

Oh, so many. I think we have moved into a new era where record production is not as clearly defined as it was and we will see more and more slash producers – artist/producer/video director etc. I only see that as a good thing. When I sit down in my studio I still am amazed at the power of software recording

Do you listen to much new electronic pop music these days? Is there anyone who has caught your attention that you enjoy?

I have very wide taste in music. I’ll jump from Beethoven’s Ninth to early 20s recordings of jazz. I have been immersed in jazz for quite a while again because I am producing a boxed set called Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology that covers the history of jazz from 1917 to 2005, 111 artists and a 200 page book. Obviously I get to hear a lot of roots music and world music being at Smithsonian Folkways but we also have early electronic stuff – John Cage etc.

I do hear new stuff that I like. I think that one of the dangers is that when so much is possible – samples of all kinds of sounds are available online and software synths and keyboards can emulate anything – things can start to get samey. It usually takes someone to come along and work within economic, technological or self imposed limitations to create something that is really different and stimulating. There has always been a tendency for record labels to sign the epigones and overlook the innovators and the originators.

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its sincerest thanks to Richard James Burgess

‘From The Tea-rooms of Mars To The Hell-holes Of Uranus’ is still available digitally via Cherry Red Records

http://www.burgessworldco.com/

https://twitter.com/richardjburgess

https://twitter.com/Landscape_band

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

27th July 2010

Follow Us!