“Hey, Do You Think I Should Do One More?”

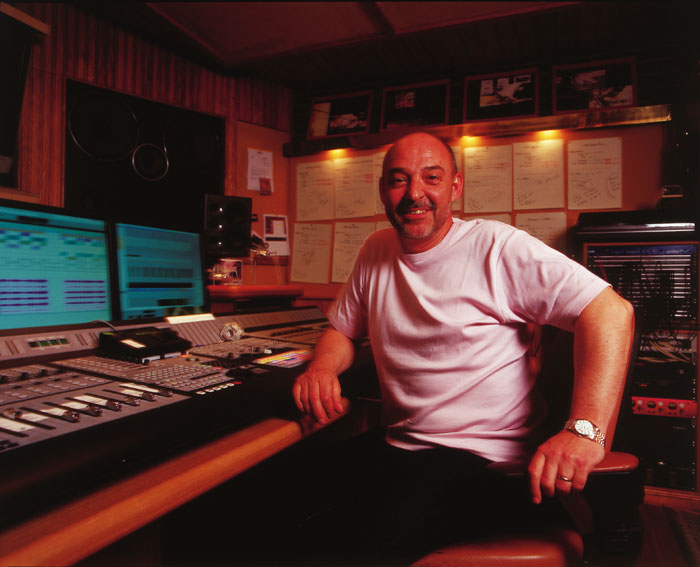

Gary Langan, along with JJ Jeczalik, Anne Dudley, Trevor Horn and Paul Morley is one of the founder members of THE ART OF NOISE.

He cut his teeth in music working as a tape op with renowned producers Mike Stone and Roy Thomas Baker for QUEEN.

He later progressed to being assistant engineer for THE BOOMTOWN RATS. In 1979 he met Trevor Horn, then of BUGGLES and engineered their album ‘The Age Of Plastic’ which featured the No1 single ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’.

One of the drummers on those BUGGLES sessions happened to be electronic music pioneer Richard James Burgess who later demonstrated his brand new Fairlight CMI to Horn and introduced his trainee programmer JJ Jeczalik who had originally been Burgess’ roadie. Continuing to work with Horn on his productions for ABC’s ‘The Lexicon Of Love’ and Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Duck Rock’ along with Jeczalik, Langan met Horn’s orchestral arranger Anne Dudley. The team ended up working with YES and the rest, as they say is history.

Langan is also a producer in his own right and his varied credits have included ABC’s ‘Beauty Stab’ and ‘Traffic’, SPANDAU BALLET’s ‘Through the Barricades’ and ‘Heart Like A Sky’, PUBLIC IMAGE LIMITED’s ‘Happy’ and THE ALOOF’s ‘Seeking Pleasure’. More recently, he has discovered a passion for front of house at live performances, looking after the sound on the Jeff Wayne’s ‘The War Of The Worlds’ tour and ABC’s performance of ‘The Lexicon Of Love’ at the Royal Albert Hall in 2009 where the incumbent BBC Concert Orchestra was conducted by Anne Dudley.

With the release of the new ‘Influence’ collection, ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK caught up with Gary Langan to go back down the avenues of history for an insightful interview that cleared up a few of the myths that have arisen around THE ART OF NOISE.

How do you remember the genesis of THE ART OF NOISE?

It happened because of a happy accident. I’d been working with Anne Dudley and JJ Jeczalik, we were like Trevor Horn’s backroom boys/girl’ working on an album with YES that spawned ‘Owner of a Lonely Heart’ called ‘90125’. Because I was the engineer, I was the curator of a tape that had a track recorded at the famous Air Studios that YES had scrapped but the drum sound was just absolutely incredible.

I surreptitiously hid it amongst all the other tapes which I thought at some point in my life, I was going to get round to using one way or another. Fast forward a month or so, we were at Sarm Studios and everybody had gone and left me and JJ with the Fairlight CMI. He said “Let’s go” but I said “No, we’re going to stick around for a bit… I’ve got this idea!” And my idea was to sample the whole drum kit and put it into the Fairlight which nobody had really thought about doing. Everybody at that stage was sampling bits and bobs of the drum kit. I said to him “No, I want to put this whole drum kit into the Fairlight” and JJ kind of gave me this gazed look like I was mad… I said “bear with me”!

So I gave him this mono mix, he plugged into the Fairlight and I asked him to sample me a bar because we only had one and a half seconds of sample at the time, so I reckoned we could just about get a bar in. And JJ, bless him, not being very musical made a happy accident of hitting the ‘go’ button on beat 3 and not beat 1 of the bar! So when he played it back to me, I now had this drum groove that was effectively backwards, it was going “3-4-1-2-3-4-1-2” and I said “you’re a genius!” He looked at me again and said “what do you mean?” and I said “you’ve got it wrong but it’s brilliant!” *laughs*

And I said “OK, now let’s put some of those wacky things that we’ve sampled from when the Fairlight was living round at my house” because JJ used to rent a room from me. The sounds happened to be a guy trying to start his VW Golf and other bits that we’d had a go at sampling. So we stuck around that night and did the demo that became ‘Beat Box’.

A couple of weeks later I was driving Trevor around, he’d been asked to start this label by Chris Blackwell of Island Records and he’s looking and searching, thinking in his head “what am I going to do as a first signing?”. So I played him this demo that JJ and I had done in the car. He went nuts and gave it to Chris Blackwell, he took it to New York that weekend and played it out in a few clubs. He came back and said to Trevor “You’ve got to do something with these guys, this is where you start!”. So that was the manifestation, that was the beginning!

‘Beat Box’ was the song that scared the life out of KRAFTWERK wasn’t it?

Well it did, but I was actually a bit of a KRAFTWERK fan to be honest so there are influences in there obviously. I think it scared them but they just didn’t have the equipment that we were privy to. But if it wasn’t for JJ being the operator and Trevor buying the Fairlight, I don’t think it ever would have happened.

What was the collaborative dynamic between you, JJ Jeczalik and Anne Dudley musically? Did you attain specific roles or did you yourself also get involved in programming the Fairlight for example?

No, we had very definite roles. I was Trevor’s engineer, JJ was the master of the Fairlight and Anne was the master of melodies.

And none of us crossed over and that’s how the chemistry of the three of us worked.

How did Trevor Horn and Paul Morley eventually fit into all this? Obviously Trevor was the producer…

Well, he wasn’t the producer!! I’m going to put the history straight there… we were the producers!! If I’m being really honest, we were a little naive. Anne, JJ and myself really had no intention of forming a band, it was as I said, a very happy accident. So when we signed to ZTT, we needed somebody to do all the artwork and how it was going to portrayed which was really down to Paul and Trevor. So out of a sort of a friendship thing, we said “you might as well be part of the band”.

I have to say that it was Paul who came up with the name, and it was Paul who did all the artwork and copy that went on the subsequent albums. The idea of the fantastic photographs taken by Anton Corbijn, that was all totally Paul. Trevor, he really wasn’t the producer, we were. He came up with a few ideas that we then explored, but because it was his label and everything, we then became a band of five. But Trevor and Paul were never in the studio. As far as studio work went, it was always Anne, JJ and myself.

Do you think if Trevor and Paul hadn’t been there with ZTT, that the demo of ‘Beat Box’ may not have got anywhere?

It wouldn’t have gone anywhere without a doubt! That whole ZTT scenario was absolutely amazing. The cogs were all falling into place and fitting very well together so the pair of them, Paul brought an awful lot to the project and Trevor oversaw the whole thing but we really were left to our own devices.

It was exciting time for all but what was the straw that broke the camels back when you, JJ and Anne decided to leave ZTT?

It was politics and money which is usually the driving force behind anybody jumping ship from a project whether it be music or a day job. It usually comes down to those two things, it was clearly obvious that our relationship with ZTT had actually sadly in some respects come to an end.

But you had the last laugh when ‘Peter Gunn’ was a hit with Duane Eddy on board and won a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental Performance? How did you meet Duane?

It was a bit of a full circle because when I started in the studio as a tape op/assistant tea boy/runner, whatever you want to call it, one of the first people that I was in the studio with was Duane Eddy. But you’re going back to 1973-74! Fast forwarding, we left ZTT and signed with Derek Green and China Records.

Derek was also very astute and realised that one of the ways forward for this band was to have collaborations. So it was Derek’s idea that we do a version of ‘Peter Gunn’. We sent a demo to Duane and he obviously said yes and at that point we were recording in Anne’s house in Sarratt, Hertfordshire. There wasn’t really a studio area, she just really had a small control room because everything we did was via the Fairlight or synthesizers and things like that.

It was in the winter and Anne, being a bit on the tight side wouldn’t put on the central heating during the day. So Duane turned up and stayed in a local B+B believe it or not! I set him up in Anne’s living room and Duane stood there in this huge sheepskin fur coat, a Fender Twin and this beautiful Gretsch guitar with this rhinestone guitar strap and did what Duane did! He played the riff on the two bottom strings of this Gretsch.

Duane’s phrase “Hey, do you think I should do one more?” that was put on one of the 12 inch mixes of ‘Peter Gunn’ became a music industry in-joke didn’t it?

Yeah, I think we made lots of jokes at the time! *laughs*

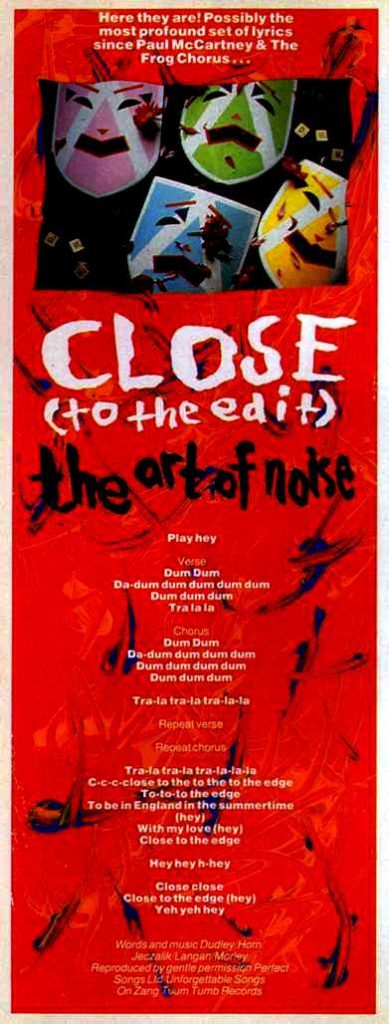

I think the funniest thing was when Smash Hits printed the lyrics of ‘Close (To The Edit)’!

I think the funniest thing was when Smash Hits printed the lyrics of ‘Close (To The Edit)’!

What did they print? *laughs*

It was “dum-dum, da-dum-dum-dum-dum-dum”!

*laughs*

But speaking of this “Hey, do you think I should do one more?” thing, do you agree with David Sylvian’s synopsis is that a recording is never actually finished, merely abandoned?

I sort of jump between two mountains if you like, I am a great believer of the first take. As a recording engineer, I truly believe and I could clarify this with loads of examples but I won’t… the first take is actually, if you’re dealing with someone who knows what they’re doing, the best.

We can run the 100 metres and get it done, and that would be the first take. Or we go and do the marathon. You can win both races but which route do you want to go?

We can do first take, or we can go round and round and round and I can guarantee you after you trying something for two more hours, I’ll play what you’ve just done and what you did two hours ago and there’s not going to be too much difference between the two performances. It was Duane saying it more out of politeness because as far as we were concerned, it was done! Bish-bosh-bash!

Was there any point with the endless remixes that you just thought “ENOUGH”?

Some of the time, after the third or fourth call for yet another remix, which is what ZTT were good at, of say ‘Moments In Love’, it was like “WHAT ARE WE GOING TO DO NOW?” And the last version, I said “let’s just play it back at half speed and see what that does!”. You get pushed and we were always good to respond to a challenge.

But some of them worked really easily, sometimes it really was kind of like pulling teeth… “OH MY LORD!! 11 O’clock, we’ve been at this seven hours and got nowhere!” It was fun though, it was breaking new ground. Doing something that other labels weren’t really doing and then they jumped on the bandwagon.

THE ART OF NOISE had that quite staccato sound because of the short sample times and that was quite unique.

We were just limited by technology. Now, you can go to Currys or PC World and buy a Mac or a PC and I can get you a bit of software and interface and you can sample half an hour if you want! We were driven by the limitations of the technology which I always thought was really good. Sometimes I think now youngsters have too much choice. They don’t get the opportunity to really work something to its limit and really start squeezing it. And that’s when things start to happen.

That’s quite Eno-esque what you just said there

Well, it’s true, I like Brian Eno. We made an album together JAMES’ ‘Pleased To Meet You’, I got on well with him.

You left THE ART OF NOISE in 1987 following working on SPANDAU BALLET’s ‘Through the Barricades’ album. Why did you leave and are there any regrets?

We had a difference of opinion which happens in every walk of life. We were offered a tour in America and the way our manager at the time wanted it, it was to do a college sit down audience tour. And I said “that’s rubbish”, I felt we needed to be more innovative when it came to touring.

So I suggested that it should be ‘THE ART OF NOISE Plays Manhattan’ and we should set up in a club called Danceteria and employ VJs and use ENG (Electronic News Gathering) cameras and microwave links so that we can actually play in four or five clubs at the same time. And what the VJs would be used for is they’d get camera shots of the audience in all the other clubs and we would make those people famous for five minutes. What I wanted to do was play on the Warhol thing of everybody will be famous for five minutes of their life, that would be groundbreaking. A sit down tour? Anybody can do that!

The other two were swayed in the other direction and I went “I don’t agree!”. At the same time, I was due to go off to Europe with SPANDAU BALLET for their ‘Through The Barricades’ tour. So we parted company at that point, although I did kind of come back and recorded a final concert at the Hammersmith Odeon or whatever it’s called! *laughs*

But no regrets. Sure, made some bad decisions, gone down some wrong avenues but as long as you learn from it, no regrets really.

‘Influence’ is an ideal way of re-evaluating the legacy of THE ART OF NOISE. What do you think the band’s ultimate contribution to music is?

I think in terms of contribution, what we showed was as long as you’re dedicated and passionate, you can do anything you want to do. I think we showed that to a lot of youngsters that came up after us like THE PRODIGY and 808 STATE, bands like that. Even when I listen to PROPAGANDA, I can hear influences form THE ART OF NOISE in their music.

Did you work on PROPAGANDA’s ‘A Secret Wish’?

Yes, I did! I did some low level engineering for them. It’s not credited, but the assistant that I trained Bob Kraushaar was the main engineer. It was low level stuff but because it was centred around the ZTT Building, then I’d dive in and help out. I did some remixes. The whole ZTT outfit was just one really big family and Trevor’s ethos behind it was he wanted to have something that was identifiable as ZTT like when you heard Tamla Motown… you didn’t know who the artist was but in the first twenty or thirty seconds you’d realise it had come out of Tamla Motown stable.

And what tracks hold the most affection for you?

Well, obviously the two early ones ‘Beat Box’ and ‘Close (To The Edit)’, ‘Moments In Love’ and then there was a track that Anne and I did that was called ‘Opus 4’.

We took this very famous poem November by Simon Armitage and I had this idea where we got Camilla Pilkington-Smyth from the Pilkington Glass family to read it three or four times. I took one line and said “that’s going to be my bass drum” and took another line and said “that’s going to be my snare drum” and I built up this whole track. I got Anne to do some fantastic melody stuff over the top. So those are the four tracks that really hold it for me.

Is Camilla the posh girl on ‘Close (To The Edit)’?

Yes, and she’s the girl that said “HEY!”

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its sincerest thanks to Gary Langan

Special thanks to Richard James Burgess for the additional information

Photos with thanks to Peter Ashworth at https://www.ashworth-photos.com/

‘Influence: Hits, Singles, Moments, Treasures’ is available now on Salvo/Union Square as a deluxe 2CD set

https://www.facebook.com/artofnoiseofficial/

http://www.theartofnoiseonline.com

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

8th August 2010

Follow Us!