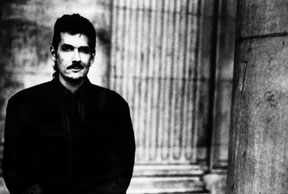

Blaine L Reininger’s roguish moustache and dinner jacket were a familiar sight in post-punk Brussels.

The American singer and multi-instrumentalist had crossed the Atlantic with TUXEDOMOON, the band he founded with Steven Brown in 1977, and become an exile of circumstance. Unable to afford the return fare to San Francisco, Reininger became an accidental European.

Falling in with the Crépuscule and Crammed Discs sets, he recorded iconic albums of genre-crossing material, both as a solo artist and, despite a period of estrangement, with TUXEDOMOON.

We find Reininger based in Athens, shorn of his moustache and recently married to his long-time partner, Maria Panourgia. Green tea and cycling have replaced the fuels from his time in the Low Countries, and he’s been working on the stage and in film, but making and performing the music of TUXEDOMOON is his ever-fixed mark. Their latest release is the soundtrack for Peter Braatz’s documentary film, ‘Blue Velvet Revisited’, made as a collaboration with CULT WITH NO NAME.

Put together for the thirtieth anniversary of David Lynch’s ‘Blue Velvet’, the film features previously unseen footage taken on set by Braatz. The album, issued by Crammed as Vol. 42 of its respected Made to Measure series, also includes a contribution by John Foxx. We asked Reininger how the project came about.

There was an outline of the project, and we settled on trying to do what we could when we could. It’s always difficult for TUXEDOMOON to get further work, because we’re spread out all over the map, really. Steven Brown is in Mexico. You’ve got me here in Athens; Peter Principle on the East Coast, between Virginia and New York; Bruce Geduldig in California; Luc van Lieshout in Belgium – he’s the only one left in Brussels, even though Brussels is like our rolling headquarters. In order to work on the project, we had to steal the time from our tour itinerary.

So, for instance, we were playing here in Athens, so I found a guy that had a rehearsal studio who is a TUXEDOMOON fan. We set up here in Athens and started to work in our usual fashion – we jam. We’re a jam band. We’ve been doing it for so long, it’s almost instinctive. We can do a lot in a short period of time.

We only actually played together for a couple of days. We had a couple of sessions – five or six hour sessions. We were working with tracks that Erik had already sent us, and we were just busting our faces off for two days. We took some of those recordings and sent them over to Erik. They had to exercise some editorial control, and they decided what they liked.

The next time we were able to do that was in Brussels, which was also on days off during the tour. It’s usually the only time we are able to all get together. Somebody has to pay for us to be together. We have to get rehearsal studios. If it takes any more, it’s us – we pay. It’s touring that funds the whole deal. So that’s what we did – we further refined our contributions to the project in Brussels.

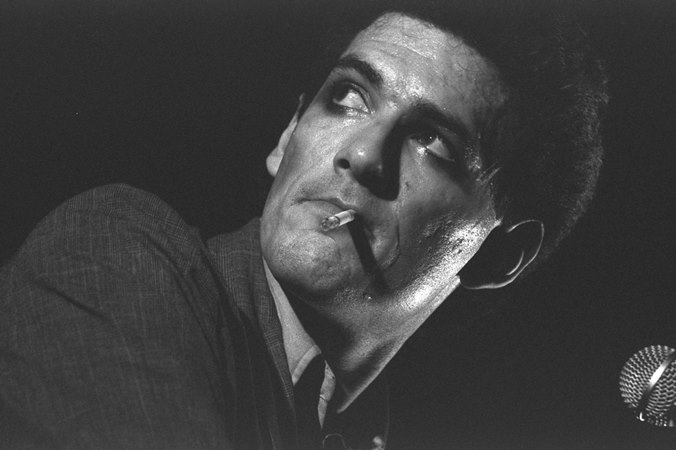

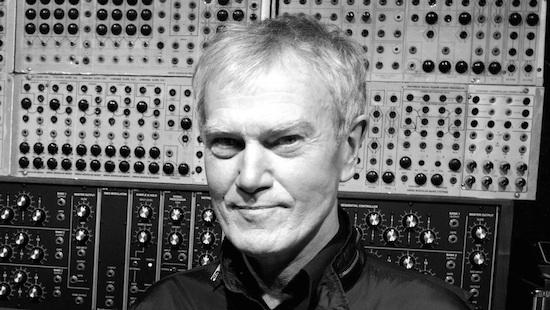

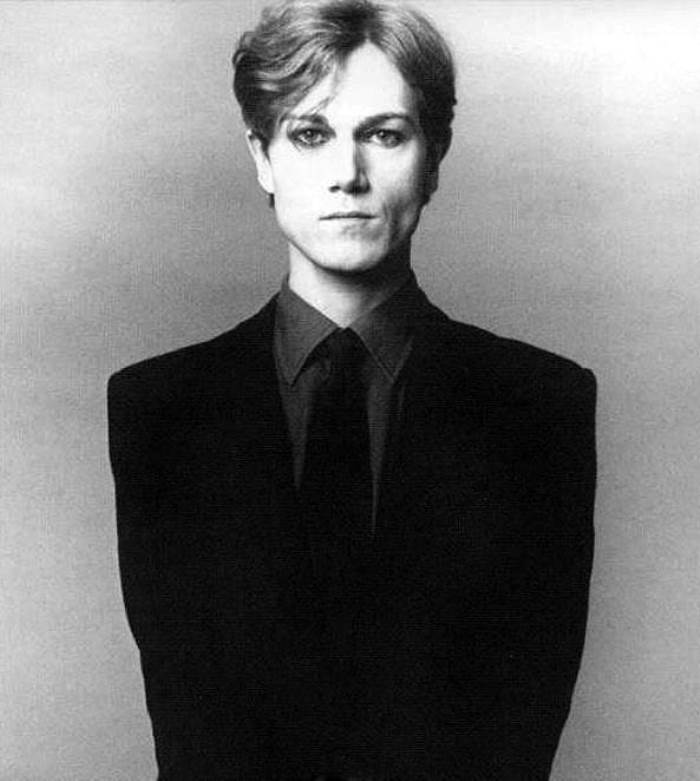

The inclusion of a John Foxx track might be presumed to come from another of Erik Stein’s connections, but the links between Foxx and TUXEDOMOON go back a long way.

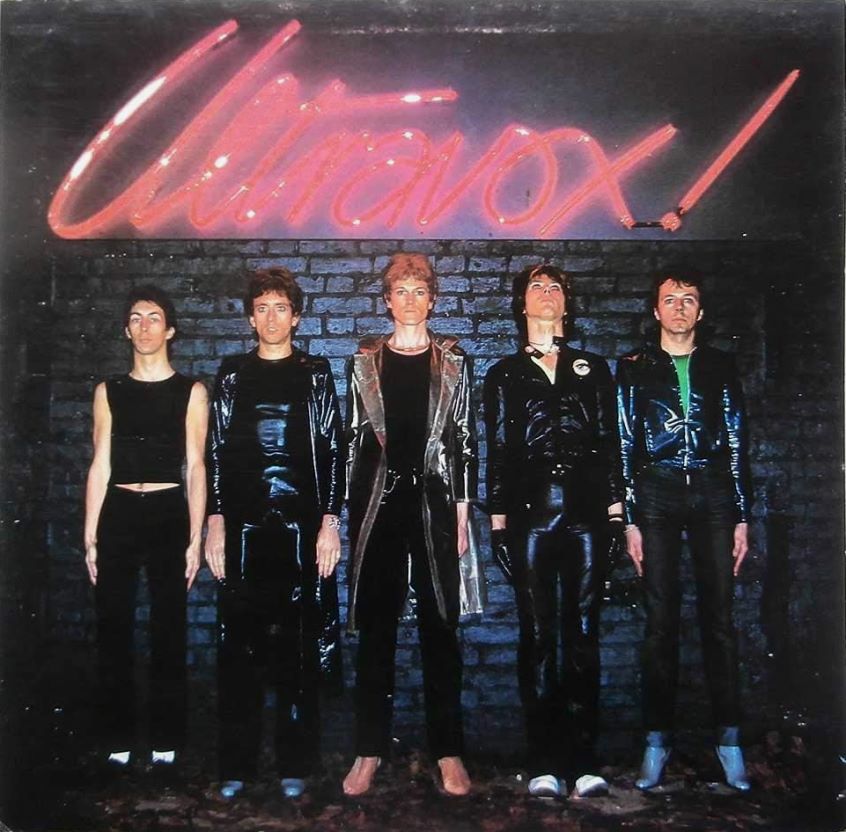

In the 80s – 80, 81 – both ULTRAVOX! and TUXEDOMOON were more in the media eye. We contacted each other by reading interviews with one another. We saw an interview with John Foxx in – I don’t know what – the NME, what have you, and they said, “What American bands do you find interesting?” He said, “This TUXEDOMOON I find very interesting.”

We said similar things. We liked what he was doing. We liked ULTRAVOX! I did, anyway. I was always a massive fan, when he was in the band, and I liked what he did after he left the band, as well. There is a certain amount of influence – there are certain commonalities between, say, ‘Metal Beat’ and ‘Desire’. We were using the same gear, for that matter – the CR-78 village, in particular, causing a lot of these sounds.

So, when we started working with an English record company, Charisma, we wanted to contact John Foxx, and that’s what happened. As it turned out, he was not able to participate in the recording of ‘Desire’, except to put us together with Gareth Jones, of course, which was a big plus. Gareth was brilliant, fabulous. Of course, he went on to do a lot of work with DEPECHE MODE. He kind of defined their sound. Working with him was really marvellous. He was able to teach us; kind of organise us.

Of course, we always knew a lot about recording from the early outset – TUXEDOMOON was a studio group at the beginning. Stephen and I were both working in his rudimentary TEAC four track studio at school, and we continued to do that with his four track tape recorder. From the outset, TUXEDOMOON was a studio band, really. So, we already knew quite a bit about multitrack recordings. Desire was our first 24 track experience. That was mainly aided by Gareth’s input.

Recorded in a studio installed in a Surrey farmhouse, ‘Desire’ was TUXEDOMOON’s second album. Tracks like ‘Incubus (Blue Suit)’ capably channelled the coldness of Foxx’s ‘Metamatic’, while ‘Holiday for Plywood’ took Dave Rose’s ‘Holiday for Strings’ deep into quirk-funk terrain. ‘Desire’ demonstrated that the psychedelic world of TUXEDOMOON was capable of absorbing and processing incidental music and futuristic pop without being precious about the boundaries between them. Jones’ contributions led to further involvement in Reininger’s solo work.

Of course, we became friends. TUXEDOMOON would often become friendly with the people we work with; so, when I was doing my second solo record outside of TUXEDOMOON, I had to write to Gareth to come along. I asked him if he would do it, and that’s what happened. He came over to Brussels and we recorded ‘Night Air’ together, which was a marvellous experience.

Gareth had really excellent production ideas that I had never thought of. He would take an electronic rhythm machine out – by that time, I was using the TR-808 – he would take that, run it through a guitar amplifier in the studio and mic the bass kick through a bass amp. He would get a little bit of that overdrive in the package. He did things like wobble up the piano with this modulated echo sound – and that kind of stuff was all kind of new to me. We had a really good time making that record.

‘Night Air’ came out in 1984. It spawned the single, ‘Mystery & Confusion’, which was a nod to Ennio Morricone’s Spaghetti Western soundtracks but also steeped in synthesized sounds. How did Reininger, the classically-trained violinist, come to electronic music?

I have always been enamoured of electronics, and over the years with TUXEDOMOON, really. I started on a level with electronics very early on.

I was – I don’t know, 12 – and my music teacher at school used to take the advanced students and he would have these morning sessions at the school. He would play records for us and talk to us. Among the things he played was Varèse. You know, he would play that guy Varèse, and I thought, “Wow!” ‘Déserts’ by Edgard Varèse – I thought this was fabulous.

Not long after that, Wendy Carlos’ version of the ‘Clockwork Orange’ soundtrack came out. Just hearing those sounds on the radio, hearing this Moog or maybe Keith Emerson’s solo on ‘Lucky Man’ – the sound of the Moog just blew my little mind, and I resolved that I wanted it – a piece of that. As soon as I was able, as soon as I could get together the resources, I wanted to play that thing. I went to the various colleges. I haunted the electronic music labs. This guy let me play on a Moog Sonic Six at one point, at one of my schools. It was a precursor to the Minimoog. It was the first suitcase synth.

Of course, another big influence on me was when Paul McCartney came out with his first solo record, where he played everything, and I had never considered that as a possibility. But the possibility that I wouldn’t have to work with all these morons that I had been working with – that I could just do it all myself – dispense with them – this was going to be my life’s work.

And it became my life’s work – as this poly-instrumentalist solo guy. The greater part of all my solo work is just me, really, and now it is entirely me. I rarely have the means or the desire to hire people in. I will play all the guitars and I will play the bass. I will play a bunch of violins and all the synths. That’s heaven to me. I love to sit here, at this very computer, amassing the sounds. It is in the process, more than the results, where I get lost.

Unlike with other kind of work – where I’m working for somebody else, I get tired and want to go home – when I’m doing this, I’ll work twelve hours non-stop. I’ll forget to pee and everything – I’ll just get lost in the synthesis. I love the pieces. With ‘Mystery & Confusion’ in particular, it was a great delight and a great challenge to make those sounds, but the gear that I had! I had this Roland SH-101 synth…and I was so proud of myself that I was able to get this French horn sound out of an SH-101. I used it for all of the bass sounds.

I was an early disciple of this Roland sync – a pre-MIDI Roland sync. So, I had the TB-303, the SH-101 and the TR-808 all running in sync with one-another. I took the Controlled Voltage out from the TB-303 and made my own cable – I also made my own Roland sync cable, which was a pre-MIDI 3-pin DIN – and I ran all that stuff. I slaved the SH-101 to the TB-303, and I used the layered sound of those two devices to get my bass sounds. So, on that record – also on ‘Mystery & Confusion’, of course – I had some good musicians with me. I had Michael Belfer, who worked with TUXEDOMOON, and I had Alain Goutier, who is a really fine bass player – he was playing fretless bass. I had Alain Lefebvre, who was playing an actual drum kit. Alain Lefebvre has his own label, called Off, in Belgium.

The 101/303/808 combination is a classic set-up for dance music. On reflection, Reininger may be the first person to put them together for a purpose other than creating acid house singles.

That’s what I could afford. Some of the other guys around had these Oberheim rigs and stuff, but I couldn’t afford that. When I was able to finagle a publishing advance from a guy who’s now the head of SABAM Belgium – he was my publisher – I got enough money from him, and Alain Goutier worked at a music store in Belgium, so I was able to get this Roland gear at a discount. It fit my budget.

The good thing about it was that it all worked together. You could sync several devices together before MIDI. It was also superior, because the DX7 came in later and emasculated everything: it whitewashed the whole deal, and everything started to sound like the soundtrack to ‘The Breakfast Club’. I am sure there are people who are nostalgic for that 80s DX7 heavy sound, but I am not one of them. It became less interesting.

Reininger was away from the United States from 1982 to 1999. We asked: How did it feel going back? Was it like going to a different place?

Absolutely. When I went in 1999, I had been away for the better part of 17 years. I had missed the 80s in America entirely, so many things were new to me. I didn’t know what people made of me. I assumed they thought I’d been in jail, because it isn’t often that you see an old dude with grey hair who doesn’t know how to operate the microwave in the 7-11. Things like that. Some of the things that we take for granted: “What the hell is this thing?!” It was like this serious Rip Van Winkle effect. I figured they must assume I have been in the joint, which is why I don’t know anything. Then I saw the money: “Whoah! It’s all the same size and the same colour – how do they tell it apart?”

It’s a strange way to be. It’s a strange situation. It gives me this life that is in a constant state of ambivalence – of two hearts, as Goethe said. Two hearts beat in my breast. There is great longing to go home. Some of my solo work has this almost pathological nostalgia, this homesickness. I felt imprisoned. I was not able to find the means to leave Europe and go home. It was not necessarily a choice. It was that great longing to be there, and also this shock and kind of horror, and – I don’t know what – disgust – at things in America: what they did, how things had decayed under the conservatives and continue to do so.

Reininger’s presence in Athens has led to invitations to perform on stage. He has also appeared in a number of films by Nicholas Triandafyllidis. We wondered whether the roles called for performance in Greek.

Sometimes. It’s not all that easy. I did a big part in the National Theatre. I played a transvestite. That was all Greek – I did the whole thing in Greek. It was difficult – I don’t speak the language that well.

A lot of times, I will do this musical actor thing – I’ll be performing and I will be doing the music as well. I’ll be on stage, incorporated into the action, but I will also be the music director or I’ll be performing the music live. A lot of times, I end up playing a foreigner. I did two movies last summer and I pretty much played a foreigner. In one of those movies, I played a banker who came to buy the prime minister. In another movie, I played a tourist. In a third movie, I played a member of the troika. So, I play these kinds of things, and I do that in English.

Should we expect to see the theatre competing for Reininger’s attention?

To be honest, not really. I enjoy doing theatre work. It is something I can do competently – I am a theatrical kind of guy – but I don’t prefer it to music, by any means. What I rarely get to do is compose a big piece of music for theatre, give it to them, collect the money and that’s the end: that’s that; I don’t have to go to rehearsal; and I don’t have to go to any performances. That doesn’t happen all that often. Most of the time, they want me to perform – my physical presence. What I enjoy most is to sit here and fool with my computer. When it becomes necessary to get up and play my violin, I will, and I enjoy it because I can.

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its warmest thanks to Blaine L Reininger

‘Blue Velvet Revisited’ is released by Crammed Discs in CD, vinyl LP and digital formats on 16th October 2015

http://www.lesdisquesducrepuscule.com/blaine_l_reininger.html

Text and Interview by Simon Helm

24th September 2015

Follow Us!