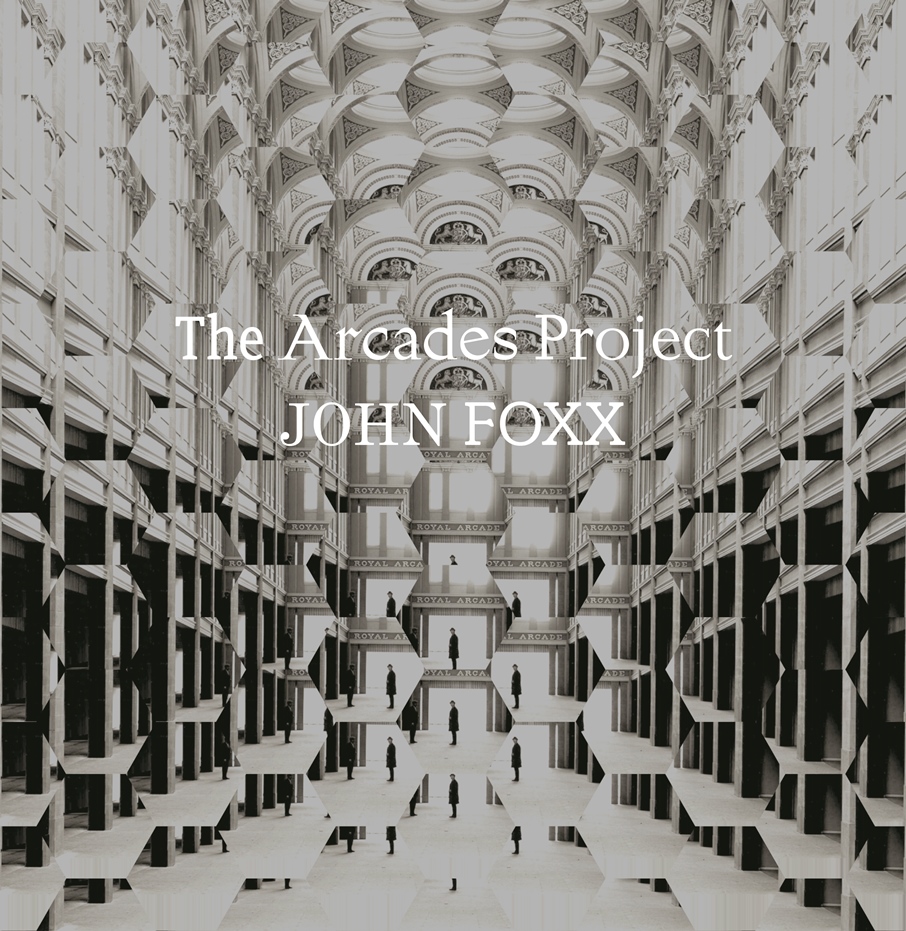

No5 in ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK’s ALBUMS OF 2023, John Foxx’s ‘The Arcades Project’ was a beautiful instrumental suite based around the piano.

In the aural lineage of ‘Transluscence’, ‘Drift Music’ and ‘Nighthawks’, ‘The Arcades Project’ can be seen as a John Foxx’s tribute to his late collaborator Harold Budd. It was inspired by Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Arcades Project’ which gathered new ideas emerging from Paris in the 19th and early 20th century,

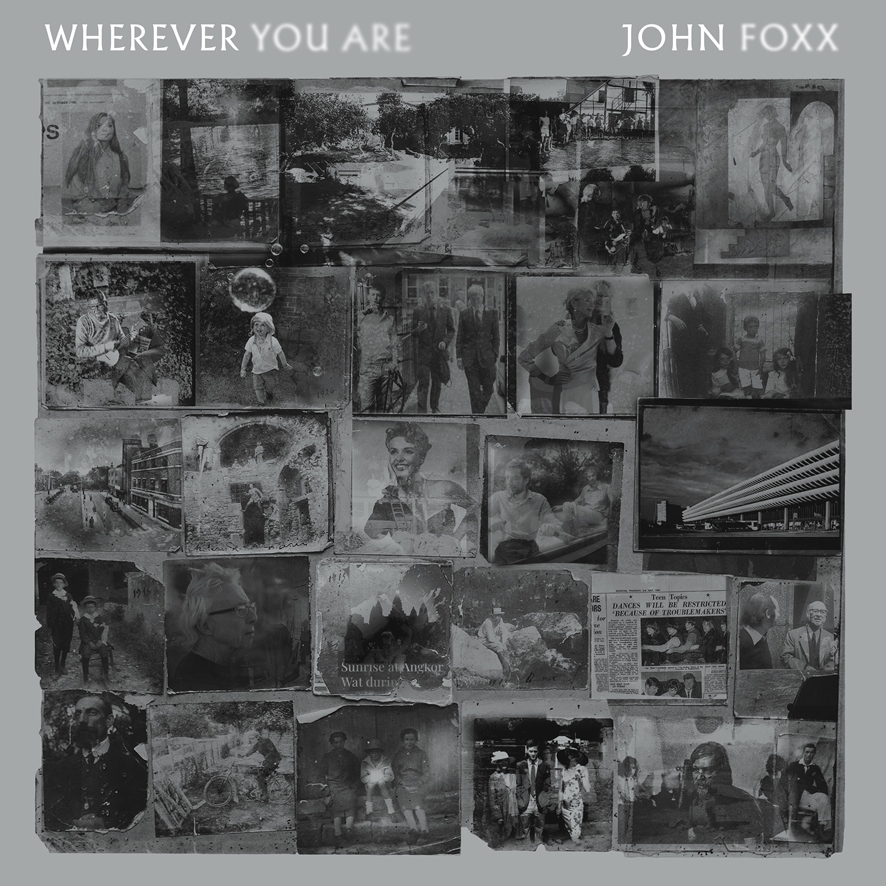

However, the new John Foxx solo piano album ‘Wherever You Are’ is a much more reflective personal work about the “mostly good, generous, bright people” he has met through his life. It was recorded at home in the weeks following a rare live performance in October 2023 as part of BBC’s Radio 3 ’Night Tracks’ event presented by Hannah Peel in London.

An album that says “simply, thanks. Wherever you are”, John Foxx spoke to ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK about the inspirations behind his wonderful ivory adventures…

Moody tracks with piano have been part of your music since ULTRAVOX! as with ‘My Sex’ and ‘Just For A Moment’, so which works with a piano aesthetic first attracted your ears?

Well, hearing a friend play a piece by Satie on the old lecture theatre piano, at art school. That was the turning point. I immediately felt I’d encountered a true, pure beauty. This was in the mid 1960s and Satie wasn’t at all well-known or well regarded then. Before that, I’d been impressed by a late-night TV series in the early 1960’s – ‘Play Bach’, by the Jacques Loussier Trio. They had a regular spot on late night TV.

From that and a few other pieces, I felt there must be something further, and I needed to hear it – a purer, less complicated sort of solo piano. It was so tantalising. A few more hints of this came from unexpected places – on the popular music front, there was ‘Cast Your Fate to the Wind’ by Vince Guaraldi, for instance. But hearing Satie made everything else fall away. That was really it.

Around the same time, my aunt gave me her old upright piano, which happened to be a reasonably good one. I was around sixteen years old. That’s when I began trying to make pieces of my own. A year or so later, at Manchester art school, my girlfriend had a copy of Satie pieces by Aldo Ciccolini – the album with the Picasso drawing of Satie on the cover. So I was able to hear more of his work. I began to wonder what form something like that might take in a modern context. A few years later, Brian Eno originated the idea of ambient music, which created a suitable context then along came ‘The Pearl’ – such a unique combination of talents – Harold Budd, quiet piano visionary, Dan Lanois, the Capability Brown of sonic landscaping, and Brian Eno, avant conceptualist. That record was really revolutionary for me – it brought Satie into the next century.

Who are your favourite piano composers?

Erik Satie, Harold Budd, some sections of Keith Jarrett’s solo concerts. After that, a few individual pieces – some Chopin Nocturnes and Debussy pieces – ‘Clair de Lune’, etc, a few slower solo pieces such as Beethoven’s ‘Fur Elise’. I also some of Arvo Part’s compositions – ‘Spiegel Im Spiegel’, ‘Fur Alina’ etc.

After ‘Metamatic’, piano made a notable return on ‘The Garden’ with ‘Europe After The Rain’ and ‘Walk Away’ but then kind of disappeared?

I had a grand piano in The Garden studio, so that was very convenient. After that, electronics took over again – there was also a period when I didn’t have an acoustic piano at home. That’s really the key – you need to be able to play whenever the mood strikes.

You did three albums with the late Harold Budd, the first pair ‘Translucence / Drift Music’ in 2003, so why have your own solo piano works taken longer to be forthcoming?

I was so completely focussed on making the work with Harold as good as possible that it took me some time to realise I hadn’t actually done a piano record of my own.

When working with Harold Budd, how would you describe your role? Did you contribute piano parts or did you leave that aspect entirely to him?

Well, I was default producer, organised the studio in a friend’s house, brought the piano over and set up recording equipment. When Harold arrived, we discussed his music – where we might take it, etc. I also recorded everything. I played around half of the piano pieces on those albums – sometimes Harold and I would swap piano chords then I’d improvise, other times I’d invent a piano piece from scratch. Other tracks were entirely his composition and playing.

Harold had the first and last word. The basic approach originated from him, a philosophy of simplicity, directness, finding the most beautiful notes, giving them space to develop, making use of the reverb and harmonic fields. We’d record as soon as it felt right. It all went very quickly and easily. The entire album was a delight to work on. Harold never played anything more than twice and mostly just once. He was so unassuming – simply came in and played, then we’d listen back and get on with the next piece.

Afterwards, I compiled what I felt were the most representative tracks and sent them off to him. He was fine with it all, so we ended up with two records, ‘Translucence’ – the piano, and ‘Drift Music’ – the more radically treated pieces. The idea of ‘Drift Music’ was complete abstraction – take reverb, echo and all sonic treatments as far as we possibly could.

By the way – It’s interesting how this has been taken even further now, by some characters on YouTube slowing those tracks down radically. I like that, and I’m absolutely sure Harold would, too. But all that’s just the technical side. The more central thing is the reason we do all this in the first place.

For my part, (and I feel this may also have some relevance to the way Harold works), it’s an attempt to capture a few small but valuable things from our passing lives. A glimpse of someone, a fleeting thought when you’re sitting on a bus looking out of the window at the city passing by, a moment of stillness and wonder, that sensation of imagining we recognise someone who vanishes in a crowd, the brief, long light at the end of a day. Nothing grand, significant or dramatic – just the opposite – and not resolved in any way, yet so recognisable when evoked musically. These small things are easily lost or overlooked, but they form a sort of undercurrent in our lives. They’re part of its fabric.

As I grow older, I begin to realise the so-called important times can often leave us unmoved, while a few odd, unexpected things will get through the defences. Some moments last forever. Music is such a great trigger, it’s capable of evoking something of the way these small things can affect us. Also, recording itself is such a strange and mysterious activity. You take a moment that would otherwise be lost forever and enable it to live forever. Isn’t that downright weird? Not to say magical?

And this can give a recorded moment vast significance. Something like using a microscope to see all the complexity inside a drop of water, or realising that a face in Cinema close-up is twenty feet high and transmitting fleeting expressions as subtle as changing weather. These recorded moments can be closely examined and re-experienced an infinite number of times, and through being captured in this way, they’ve become something quite new.

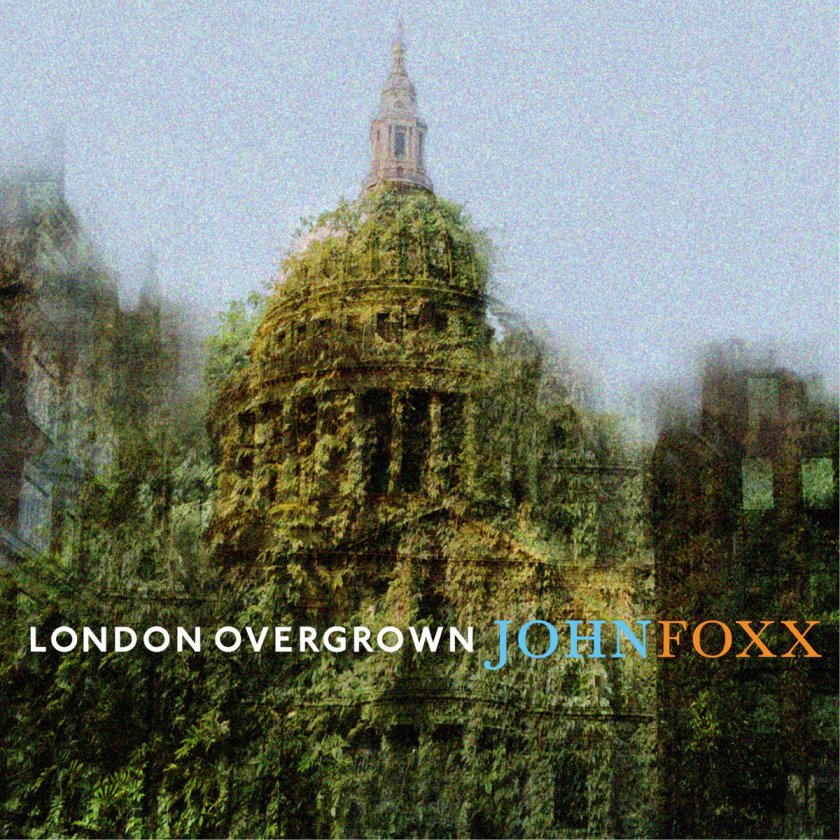

‘The Arcades Project’ was billed as your first solo piano album, how would you describe your approach? How was it different from your instrumental ambient works like the ‘Cathedral Oceans’ trilogy or ‘London Overgrown’?

‘Arcades’ is a lot simpler and absolutely direct. One instrument. All improvised. Occasionally, a discreet synth part. ‘London Overgrown’ and ‘Cathedral Oceans’ involved improvising over long delays then building multiple tracks. ‘Cathedral Oceans’ was intended as a technological continuity of ancient chant, through singing into huge, notional electronic spaces and harmonising with returning, reflected voices. Both had an entirely different premise from ‘Arcades’.

You have said that “Around dawn is the best time to play piano”, were most of the pieces improvised or was there some degree of notation beforehand, even if it was just to sketch a basic structure?

Very little was ever written down – the only time I ever saw Harold use any sort of notation was on ‘Spoken Roses’ – he referred to some brief notes he’d made, then he did two takes, one after the other, both good, before choosing one as the master. It was a revelation to hear that piece unfolding live. Truly gorgeous. Everything else sprang from a basic chord or two, then a note or two over that, then you were off – take it any way you feel. A few very basic, but vital rules – maximum beauty, minimal notes. Brevity, simplicity, joy.

In what ways does your new piano album ‘Wherever You Are’ differ in concept from ‘The Arcades Project’, it appears more personal?

Yes, I think it is.

I see Harold Budd and Conny Plank among the many photos on the front cover artwork of ‘Wherever You Are’?

Well, they’re both significant. Satie’s there too, on the inside cover. It all goes back to him.

How important is the visual presentation of these piano works to the music it contains?

I guess the imagery acts as a sort of entry point. Indicates the kind of emotional tone you can expect to encounter.

What types of piano have you been using?

A Yamaha grand, 6ft 2inches. Great fun getting it through the front door a few years ago, when I swapped it for the previous one, which was a few inches shorter. Occasionally I get access to other pianos. A Steinway or a Kawaii, and I can sometimes use a combination of sustain from an acoustic piano and play over that using Pianoteq.

In terms of recording, piano is known not to be easy to lay down and there was a time particularly when there was a lot of Roland CP70 electric baby grand piano direct input and then treated afterwards, what set-up did you use to record your pieces at home?

Simple as possible. A couple of decent mics placed inside the lid, an old Alesis mixer and an antique reverb unit. I’d begun to use some newer software reverbs, but the overall sound of the antique thing is richer, more interesting. Occasionally I’ve just used one mic, and that can be more solid an image, letting the reverbs do the stereo. You always have to move the mics around very patiently until it all feels cohesive. That’s the most important bit, really. You simply have to listen.

Although ‘The Arcades Project’ and ‘Wherever You Are’ are piano-based works, there are a lot of effects and occasional synthesizer, had you considered producing more something much barer and more minimal?

By the way, there’s no synth on ‘Wherever You Are’. It’s all piano and reverbs. I think the way I record is already fairly simple and minimal – single takes of an improvised piano piece, made mostly by reacting to the piano’s open string harmonics. You see, my basic premise is – there’s an aspect of the piano that has been completely overlooked, yet it’s what makes the piano completely unique. This is the harmonic field produced by the sympathetic vibration of all its strings.

By simply holding down the sustain pedal, you allow all the strings to make this wonderful, moving, harmonic field. No other instrument can produce an effect like that – perhaps the nearest might be a sitar – but that doesn’t have anywhere near the number of strings. A piano has over two hundred, so they produces an incredibly rich and complex sound, and I think this is the unique signature of the modern piano.

Yet no-one seems to have noticed it. No music I know of has ever been composed or recorded with this in mind – it’s simply never been investigated properly – so that’s what I’ve been doing with these recordings. The reverbs I use are designed to extend those harmonics, that combination creates a changing bed of sound for me to improvise over.

The origins of this go way back to 1977, recording the first minute and a half or so of the intro to ‘A Distant Smile’, with ULTRAVOX! I got Billy to play a few piano chords, having had the idea of getting him to hold down the sustain pedal in order to allow all the piano strings to vibrate sympathetically, then recording these until they died away, some time later. Then I asked Steve Lillywhite to take off the initial impact of the notes being hit, by fading in just the sustained sound afterwards.

In this way, we quickly built up several layers that make a beautiful bed of moving, sympathetic harmonics from the two hundred or so strings. You can hear these under the track’s beginning. I was tremendously excited by the beauty and potential of the sound this produced. It was obvious there was so much more to explore here, but also frustrating, because I couldn’t do that – we were in the middle of making a rock album to a strict deadline. So I had to stow the idea away for later use.

Have you any favourite pieces from ‘Wherever You Are’?

The first track, ‘When She Walked In With The Dawn’, because that’s when I got the sound just right, which triggered me to write and record all the other tracks.

With the piano, have you found your forte, as it were, at this stage of your creativity or is there something else you would like to try, say with artificial intelligence for example?

I do feel I’ve got a unique territory I can explore now – and that’s always a great feeling – your own territory, another adventure opens up. I like the simplicity and the entirely hands-on nature of it.

You set up the sound, than simply sit down and record – and that’s it, no overdubs or other complications, an entirely human response to what a piano and an old reverb unit gives you. It acts as a great release from all the other stuff I’m involved in. It’s the opposite of AI – and even of synths or multitrack recording. Much as I love all that, it’s just wonderful to take a step sideways.

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its warmest thanks to John Foxx

Additional thanks to Steve Malins at Random Management

‘Wherever You Are’ is released on 28th March 2025 by Metamatic Records as a vinyl LP and CD, available from https://johnfoxx.tmstor.es/

Digital download available from https://johnfoxx.bandcamp.com/

https://www.facebook.com/johnfoxxmetamatic

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

26th March 2025

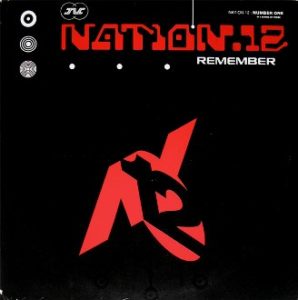

Foxx made an unexpected return to music with an acid house inspired number produced by Tim Simenon of BOMB THE BASS fame: “It was a great experience – a new underground evolving from post-industrial Detroit, using analogue instruments rescued from skips and pawn shops… Tim Simenon turned up wanting me to do some music… so Foxx was out the freezer and into the microwave…” – the other material that was recorded didn’t see the light of day until 2005.

Foxx made an unexpected return to music with an acid house inspired number produced by Tim Simenon of BOMB THE BASS fame: “It was a great experience – a new underground evolving from post-industrial Detroit, using analogue instruments rescued from skips and pawn shops… Tim Simenon turned up wanting me to do some music… so Foxx was out the freezer and into the microwave…” – the other material that was recorded didn’t see the light of day until 2005.

Follow Us!